Nei-yeh (Chinese Self-Cultivation Manual)

Verse 23. The Tao of Eating

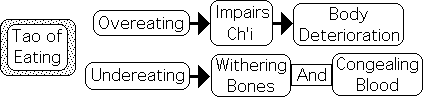

1 For all the Way [Tao] of eating is that:

2 Overfilling yourself with food will impair your vital energy (ch’i)

3 And cause your body to deteriorate.

4 Over-restricting your consumption causes your bones to wither

5 And the blood to congeal.

6 The mean between overfilling and over-restricting:

7 This is called "harmonious completion".

8 It is where the vital essence (jing) lodges

9 And knowledge is generated.

10 When hunger and fullness lose their proper balance

11 You make a plan to correct this.

12 When full, move quickly;

13 When hungry, neglect your thoughts;

14 When old, forget worry.

15 If when full you don't move quickly,

16 Vital energy (ch’i) will not circulate to your limbs.

17 If when hungry you don't neglect thoughts of food,

18 When you finally eat you will not stop.

19 If when old you don't forget your worries,

20 The fount of your vital energy (ch’i) will rapidly drain out.

Commentary

Verse 23 focuses upon the Tao of Eating. As might be imagined, this process entails finding the mean between too much and too little.

Lines 1-5:

1 For all the Way [Tao] of eating is that:

2 Overfilling yourself with food will impair your vital energy (ch’i)

3 And cause your body to deteriorate.

4 Over-restricting your consumption causes your bones to wither

5 And the blood to congeal.

The verse begins by describing the negative consequences of an excessive relationship to consumption. Over-eating impairs ch’i flow and causes the body to deteriorate. Under-eating causes the bones to wither and the blood to congeal.

Lines 6-9

6 The mean between overfilling and over-restricting:

7 This is called "harmonious completion".

8 It is where the vital essence (jing) lodges

9 And knowledge is generated.

These lines describe the advantages of attaining a balance with regards eating. The mean between these two extremes is called ‘harmonious completion’. This is where jing resides (our inner spirit house shé) and knowledge is generated.

Recall from Verse 1 that jing resides in the Sage’s center/core and in this verse the balance point between extremes. Connecting the dots, abiding in the center enhances our life force (jing), which makes us more Sagely.

The last line validates this interpretation. Besides enhancing jing, residing at the mean results in deeper understanding (knowledge generation). It seems that eating in a balanced fashion enhances both our life force and our cognitive skills.

![]()

Lines 10-11

10 When hunger and fullness lose their proper balance

11 You make a plan to correct this.

These lines acknowledge the possibility, even probability, of straying from the sweet spot between extremes. Rather ‘going with the flow’, the Nei-yeh suggests taking action – exerting some will power. If hunger and fullness are imbalanced, a plan should be made to regain our balance.

The subsequent lines delineate both some plans to maintain the mean and the consequences of not following these suggestions. The verse addresses overeating, under-eating and too much thinking.

Lines 12, 15-16:

12 When full, move quickly;

15 If when full you don't move quickly,

16 Vital energy (ch’i) will not circulate to your limbs.

‘When full, move quickly’, presumably to stop eating. If we continue to eat after we are full, ch’i won’t circulate to our limbs. In modern terms, overeating impacts our circulation. Decreased blood flow limits oxygenation, which of course diminishes both our life force and mental acuity.

![]()

Lines 13, 17-18:

13 When hungry, neglect your thoughts;

17 If when hungry you don't neglect thoughts of food,

18 When you finally eat you will not stop.

‘When hungry, neglect your thoughts’ presumably regarding food. If we continue thinking about food when we are hungry, we won’t be able to stop eating once we begin. It seems that dwelling on hunger has a tendency to imbalance our eating habits. Rather than allowing our thought trains to go their merry way, the Nei-yeh recommends exerting intentionality (the te-yi synergy) to shift attention in another direction.

![]()

This suggestion could also apply to cravings of any variety. Indulging our thought-emotions when craving something, anything, results in excessive, i.e. imbalanced behavior. Fear, greed, jealousy, and anger are just a few examples of emotional states that we should temper rather than feed with more thoughts. As the next few lines suggest, worry is another emotion that can lead to destructive consequences if not checked.

Lines 14, 19-20:

14 When old, forget worry.

19 If when old you don't forget your worries,

20 The fount of your vital energy (ch’i) will rapidly drain out.

Continuing to worry when we get old, results in jing, the fount of ch’i, draining out and drying up. The ideogram that Roth translates as ‘worry’ could also be translated as ‘mulling over’ or ‘dwelling upon’. In this case, the meaning of ‘worry’ is expanded to include any endless mental loops that repeat over and over again. Because there is no resolution, these repetitive thought chains presumably drain our mental energy (ch’i). The Nei-yeh advises us to ‘forget’ these mental states. Could shifting attention to being, i.e. breathing, aligning the body, calming the mind, be the means by which we are able to ‘forget’ and move on?

![]()

Again this statement could be generalized to include any age and any out-of-control thought-emotion. Jing, the fount of ch’i, will drain out if we don’t forget/temper our thought processes. This tempering process presumably consists of exercising the te-yi intention synergy to both restrain and redirect our thoughts.

These lines clarify a mysterious Master Ni utterance: “Forgetting very important. Easy to say; hard to do.” While important, forgetting our obsessive thought patterns is difficult to accomplish.

Stopping in perfection and controlling our thoughts are two basic techniques the Nei-yeh offers to maintain or regain balance. Flowing with our natural inclinations does not result in harmony, but instead enables the destructive mental feedback loops that are so disruptive to mental tranquility and thereby vitality. Rather than going with the flow, we must exercise the te-yi intention synergy to both restrain and redirect our behavior and thoughts. Sometimes merely redirecting our attention to sheer awareness is sufficient to halt negative pulses. By exerting will power over our thoughts we are able to regain and maintain balance.

The topic of this verse, i.e. the common everyday practice of eating, suggests that the Nei-yeh’s intended audience are not just those of mystical bent. Indeed the Nei-yeh’s self-cultivation framework applies not just to Taoist mystics, but permeates the thought and behavior of Confucians, Buddhists and Chinese culture as a whole. Due to its widespread applicability, the Nei-yeh’s generalized processes are not only designed to achieve mystical states or even inspiration, but serve as a practical guide to everyday living. This analysis applies particularly to this verse – the Tao of Eating.